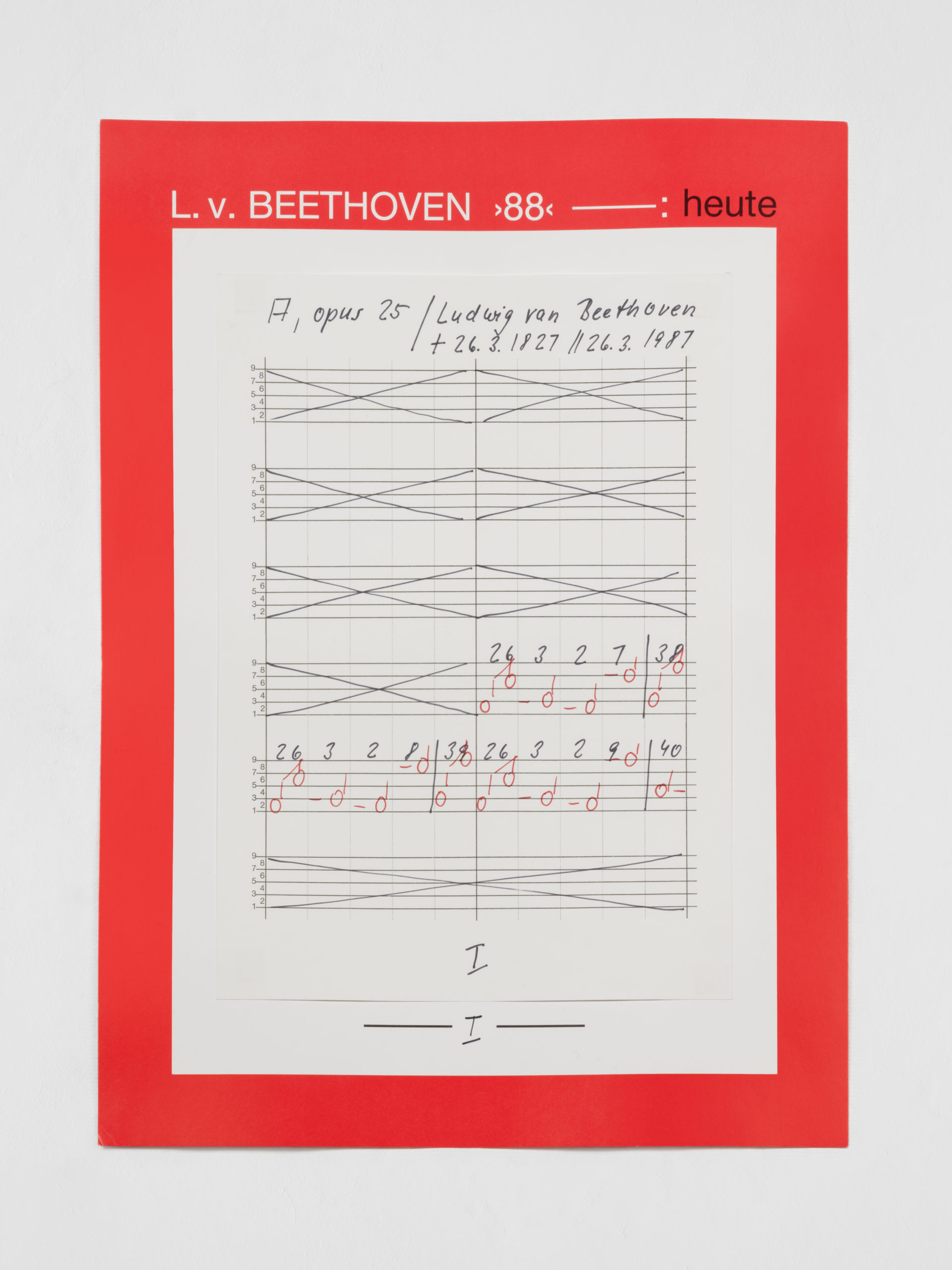

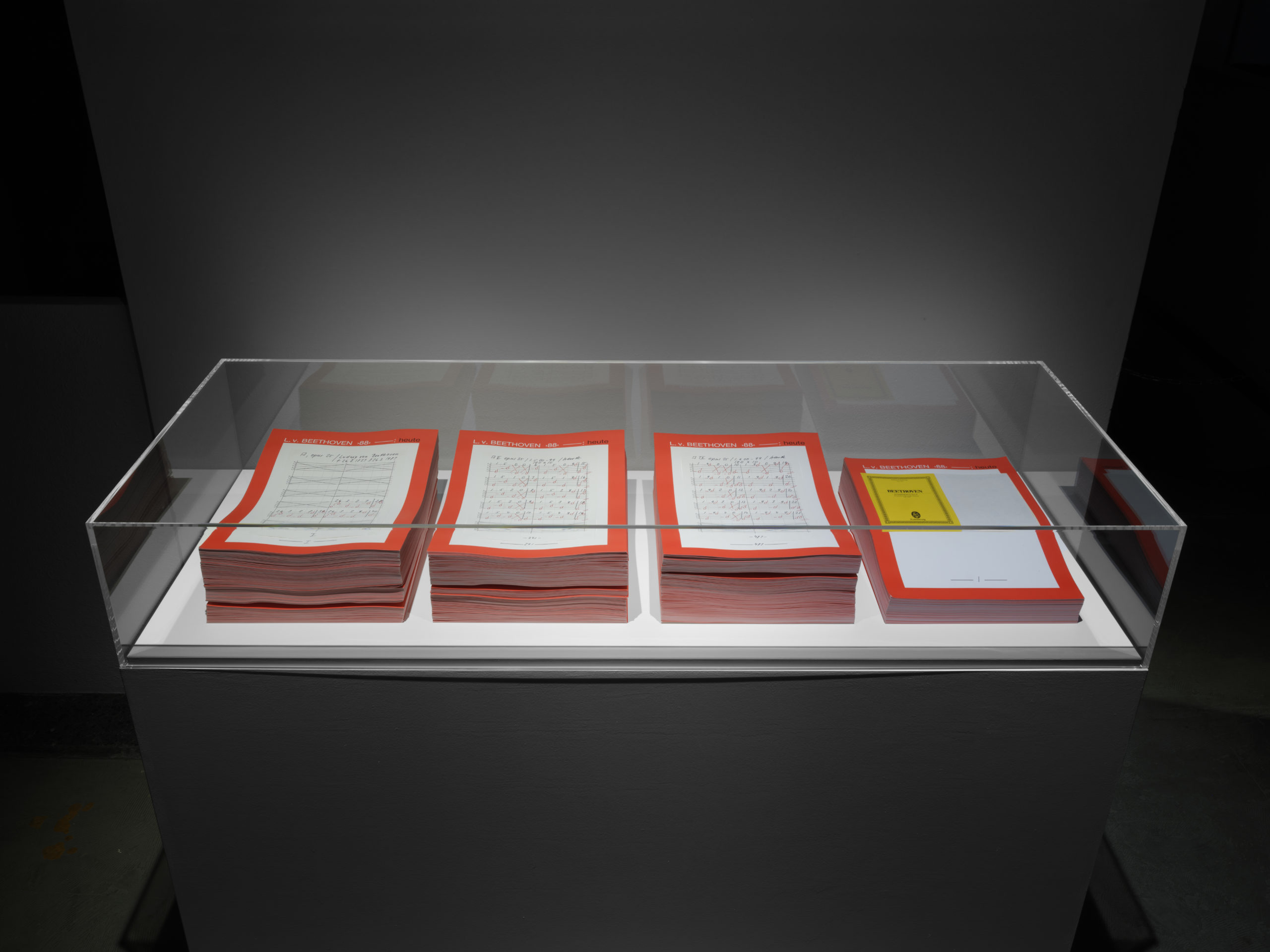

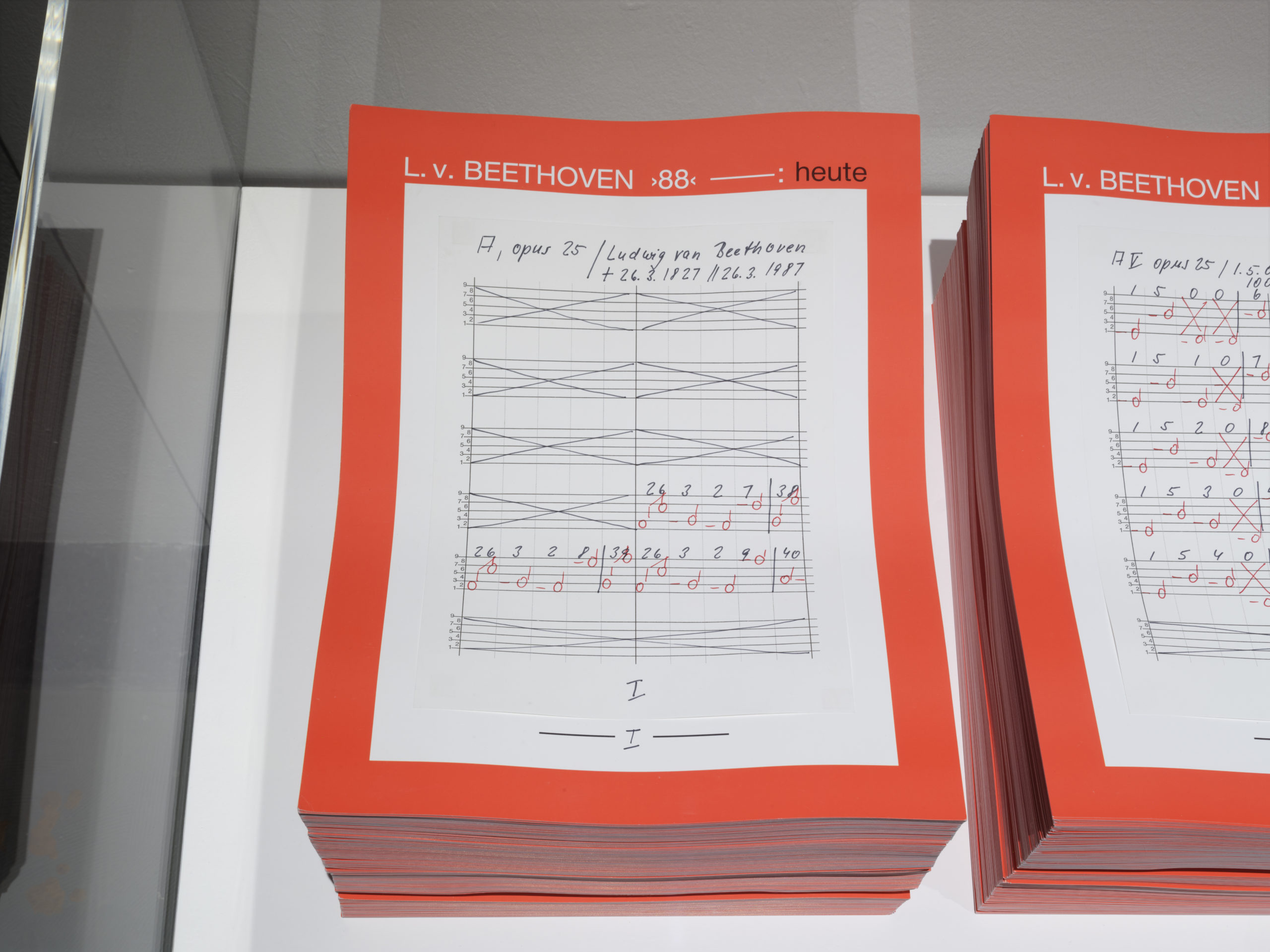

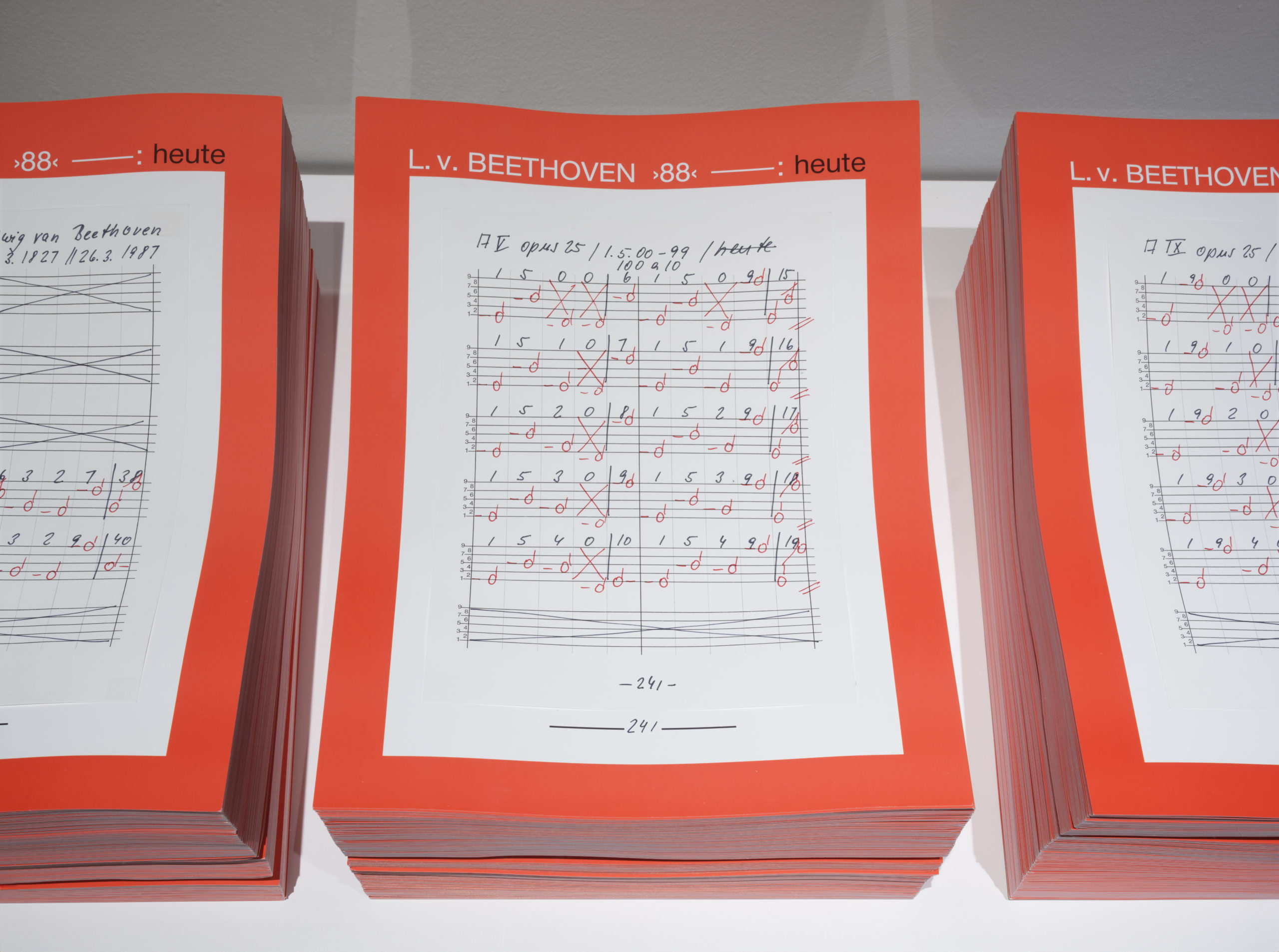

Hanne Darboven

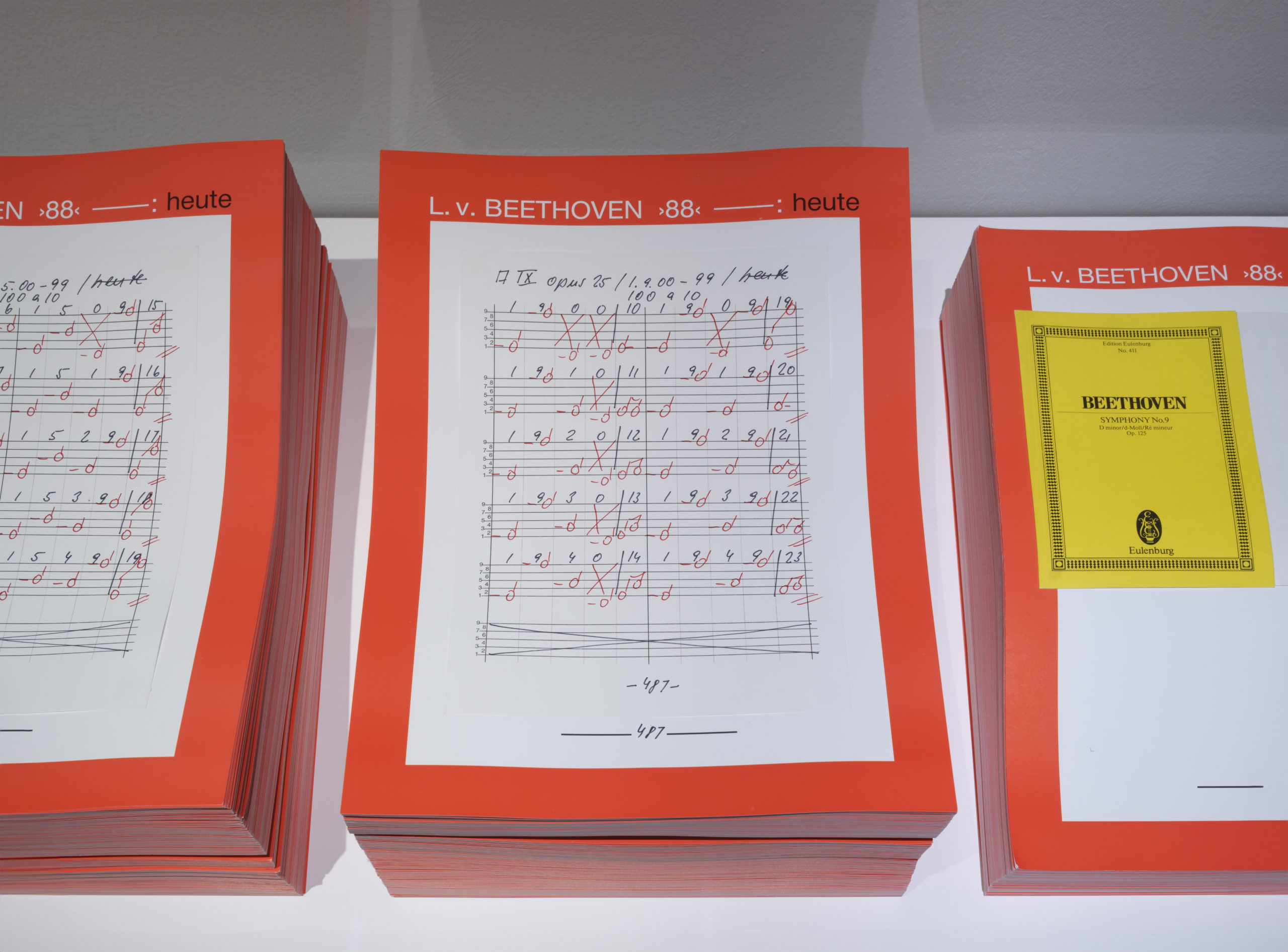

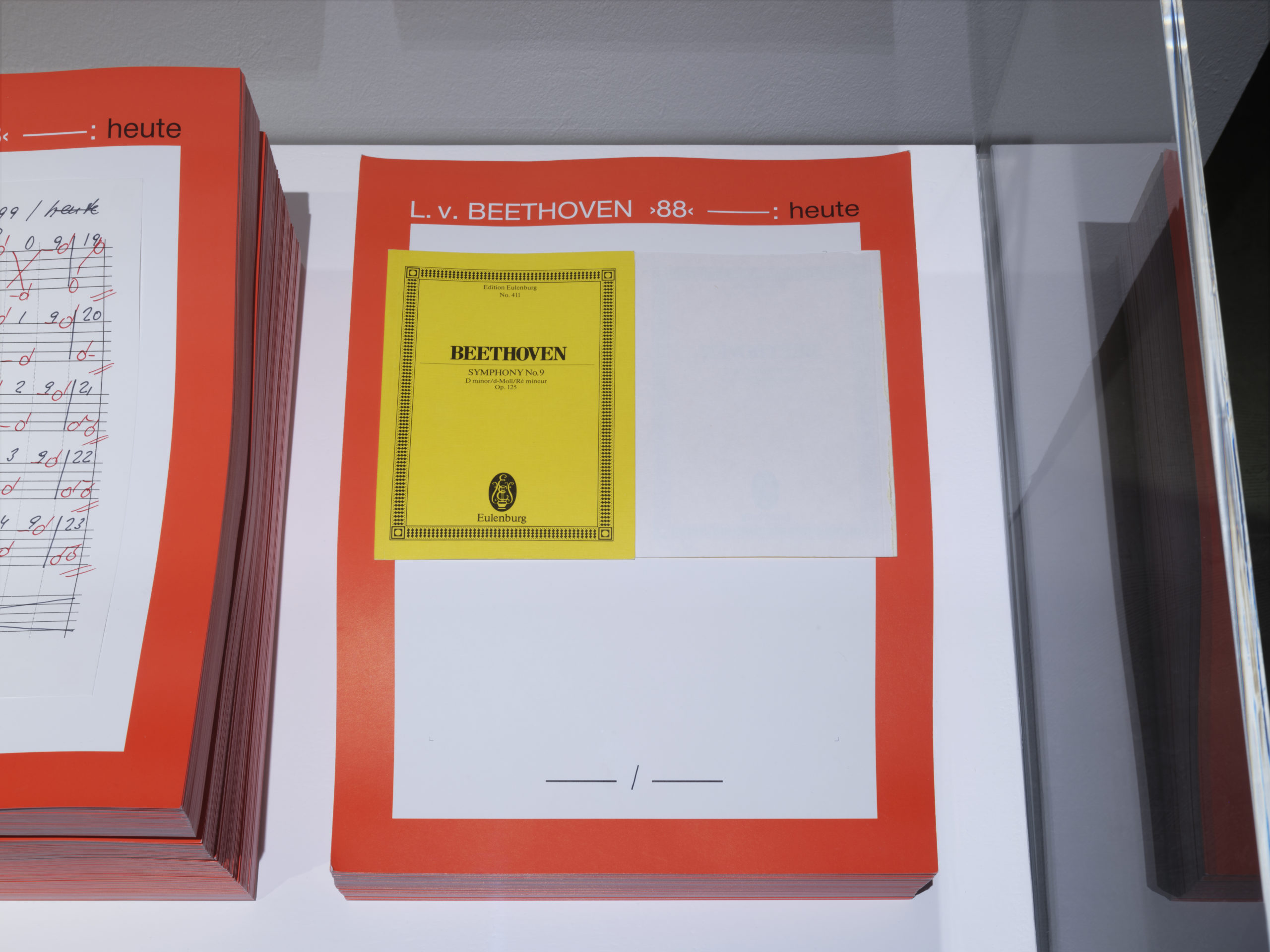

Opus 25 A “Ludwig van Beethoven”, 1987

Collage, red and black ink on music paper, handwritten score on red framed offset paper

© Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / Courtesy Sprüth Magers

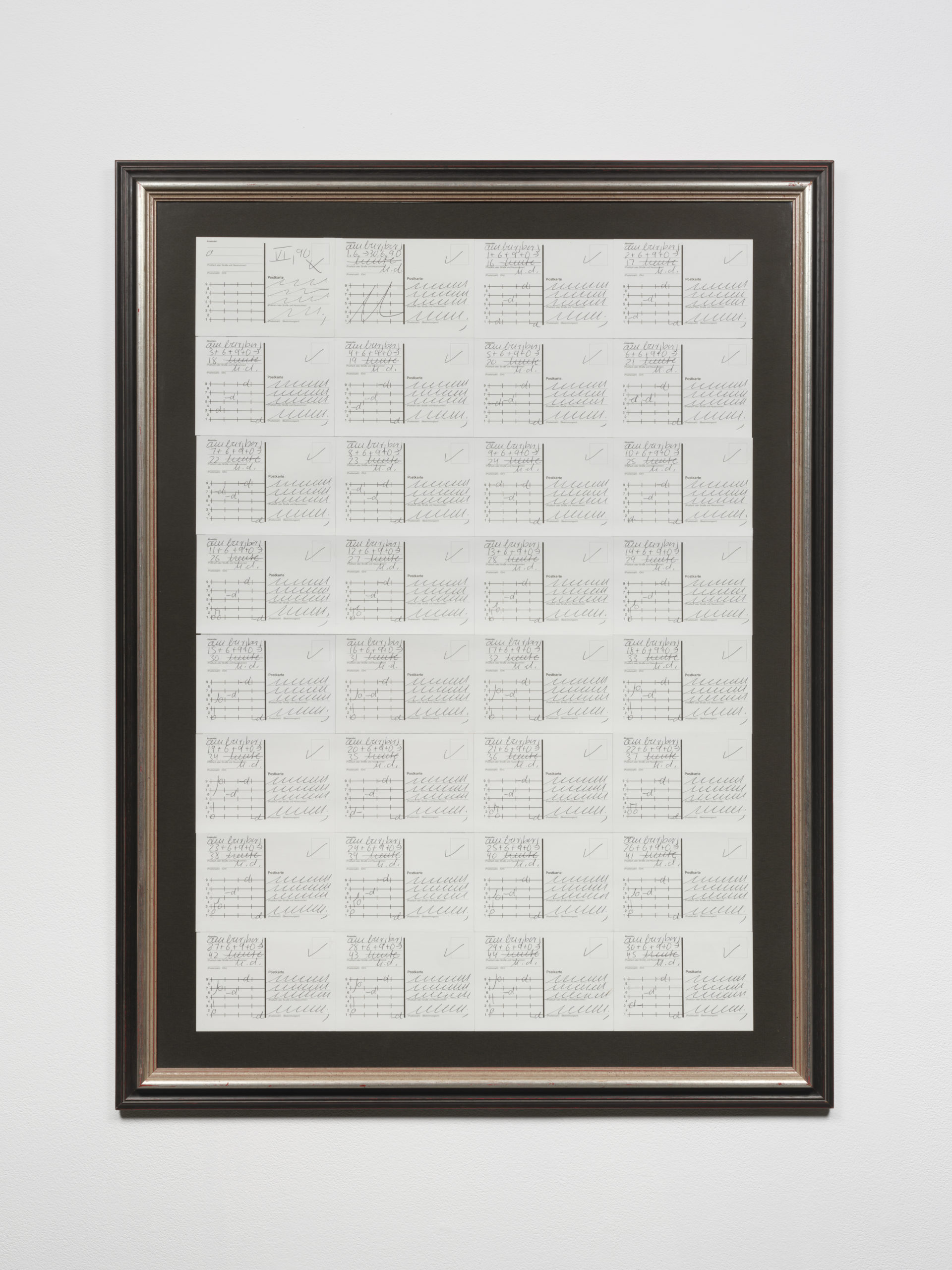

Hanne Darboven

Ohne Titel / Untitled, Monate mit Postkarten (Juni) / Months with postcards (June), 1990

Collage, felt pen

© Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / Courtesy Sprüth Magers

PRESS RELEASE

HANNE DARBOVEN

OPUS 25 A “LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN”

NOVEMBER 11 – DECEMBER 23, 2023

It is generally accepted that the subject of Hanne Darboven’s (1941-2009) practice can be broadly understood as a systematised form of “writing time”, writing in time or writing out of time. It could also be understood as a periodisation of capitalist modernity, or even a speculative investigation of time and being. For Darboven, time is both material and process and is expressed through three modalities: as subjective (or individual) time, historical (or collective) time and as objective (or institutional) time. These temporal categories are always disjunctive co-productions, troubled by collective memory and nostalgia, in a totalising image or “sound-image” of time.

But what happens when this conception of linear time is repeated? What happens when progressive or additive time becomes recursive time in a serial format? Can sequential graphic or sonic repetition generate difference and variation rather than sameness and imitation?

If the image of time in Darboven’s practice employs differential modalities, then it also requires archival procedures to inscribe its symbols and words: notation, marking, writing, counting, reading and calculating. These operations are always embedded in the spatial logic of the grid—sheet music, a calendar, a column, a block—operations that suggest an overt sense of legibility, order and rationality as a form of communication and conveyor of meaning, even if that form’s “content” appears enciphered, under erasure or temporally lapsed through her precise and idiomatic use of language, symbols (numbers or notes), squiggles and strikethroughs (“heute“), as well as her inclusion of found images and artifacts, both inside and alongside of her rows of framed panels.

If Darboven’s work is about mark-making as time, then who or what is the subject of her “writing”, of (her) “history”? Is it the artist, the viewer or listener, society at large or “Germany” itself and if they or it are the creator of this history who or what is its object? Furthermore, are these serialised histories materialist or idealist? That is, as artworks do they understand “history” as an ensemble of social relations or as transcendental forms of appearance or representation in time and space.

Darboven’s sound recording of Opus 25A for organ “Ludwig van Beethoven” (1988) is a fifty-six-minute musical composition divided into twelve sections of two or three “pages” (Seiten), representing the months of the year, spanning the entire 20th Century, each with a duration of approximately four and half to five minutes. These sections are subdivided into brief episodes composed of both arpeggios and individual notes played concurrently, with a duration of approximately ten to twenty seconds each, followed by a few seconds of silence. Each of the twelve sections or months is followed by a brief passage of notes or ligature punctuating the end of each movement, with brief passages of silence or musical rest between them. The duration of time between the sections or months, the subdivisions of arpeggios and individual notes, the passages of notes or ligatures that follow the subdivisions and the silences or musical rests, is variable.

Accompanying the recording, is the exhibition version of Opus 25 “Ludwig van Beethoven” (1987) and Untitled, Months with Postcards (June), (1990). Darboven’s musical compositions, from the early 80s onwards, were professionally transcribed into performable arrangements, her so-called “Mathematical Music”: the adaption of numbers into notes as a (open) score, which itself could be described as a “time-image,” a kind of sonic thesis on history.

David Bussel

Exhibition curated by Bill Kouligas and Benjamin Lallier