HOLDING ON TO IT

HANNE DARBOVEN / MIMOSA ECHARD / ROCHELLE GOLDBERG /

KUNIZO MATSUMOTO / ROSE SALANE / MICHAEL E. SMITH

JANUARY 27 – MARCH 5, 2022

ROSE SALANE

REPEATING THE ENCOUNTER, 2021

FOUND SIGNED CD CASES, 61 x 88.9 x 5.1 cm (24 x 35 x 2 in) EACH

ROSE SALANE

REPEATING THE ENCOUNTER 3, 2021

FOUND SIGNED CD CASES, 61 x 88.9 x 5.1 cm (24 x 35 x 2 in)

ROSE SALANE

REPEATING THE ENCOUNTER 4, 2021

FOUND SIGNED CD CASES, 61 x 88.9 x 5.1 cm (24 x 35 x 2 in)

ROSE SALANE

REPEATING THE ENCOUNTER 5, 2021

FOUND SIGNED CD CASES, 61 x 88.9 x 5.1 cm (24 x 35 x 2 in)

DETAIL: MIMOSA ECHARD

PRIVATE PICTURE 1, 2021

MIMOSA ECHARD

PRIVATE PICTURE 1, 2021

PERSONAL OBJECTS, CHERRY PITS, NATURAL DYING SILK, PLASTIC BEADS, ANALOG PRINTS, METALLIC CIRCLES, PAPER BUTTERFLY WOOL, SILK ROPE, PILLS, ACRYLIC LACKER

200 x 105 cm (78 6/8 x 41 3/8 in) approx

MICHAEL E. SMITH

UNTITLED, 2017

ALTERED SHOES, 11 x 11.8 x 7.8 in (28 x 30 x 20 cm)

MIMOSA ECHARD

PRIVATE PICTURE 3, 2021

PERSONAL OBJECTS, PILLS, WOOL, PLASTIC BEADS, NATURAL DYING SILK, NATURAL DYING LACE, SILK ROPE, TULLE, ACRYLIC PAINT, ACRYLIC LACKER

280 x 100 cm (110 2/8 x 39 3/8 in) approx

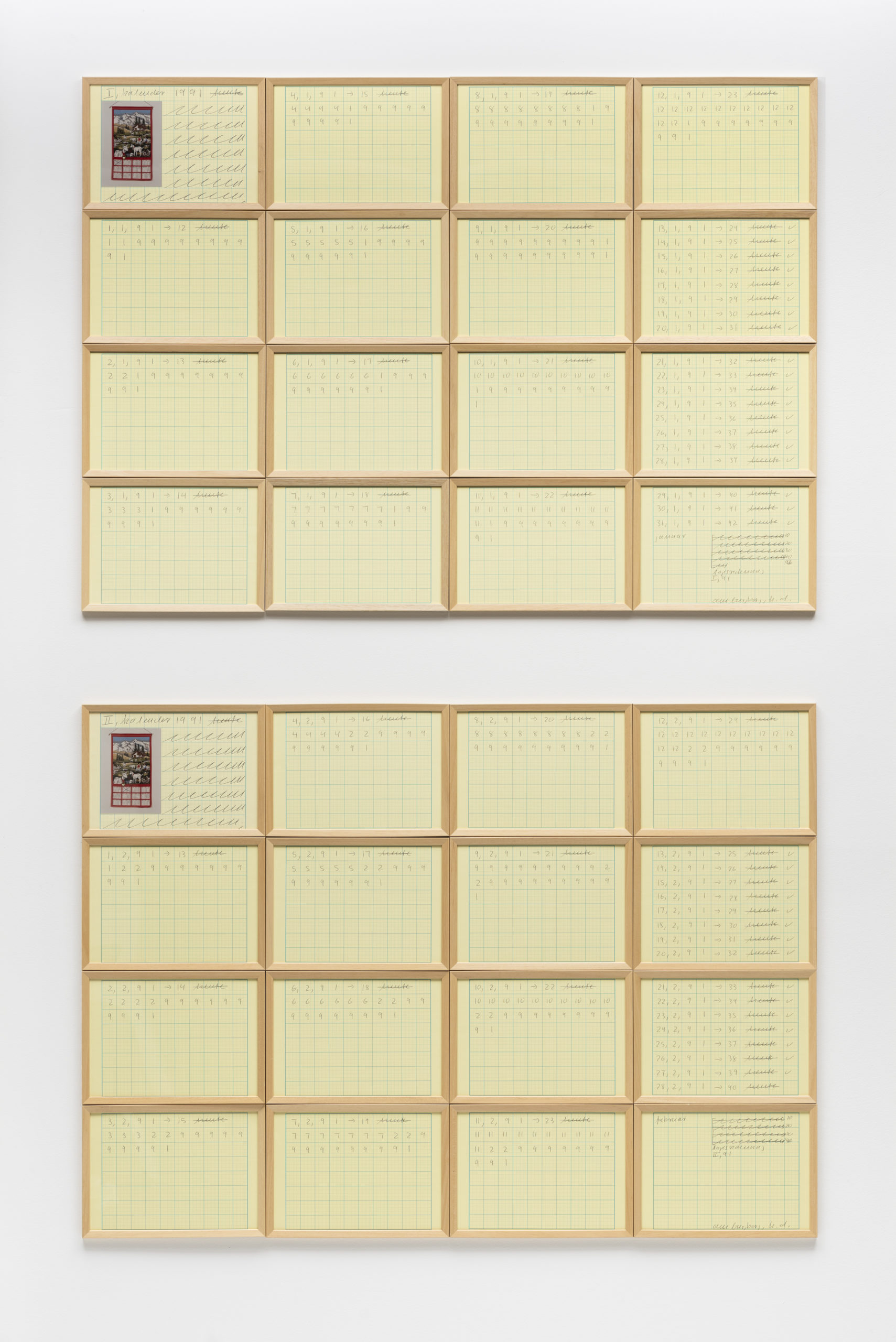

HANNE DARBOVEN, MICKYKALENDER I-XII, 1991

192 SHEETS, BALLPOINT PEN ON YELLOW PAPER, 12 COLOUR PHOTOGRAPHS

21 x 29.6 cm (81/4 x 11 5/8 in) each sheet

Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / DACS, London 2021 | Courtesy Sprüh Magers

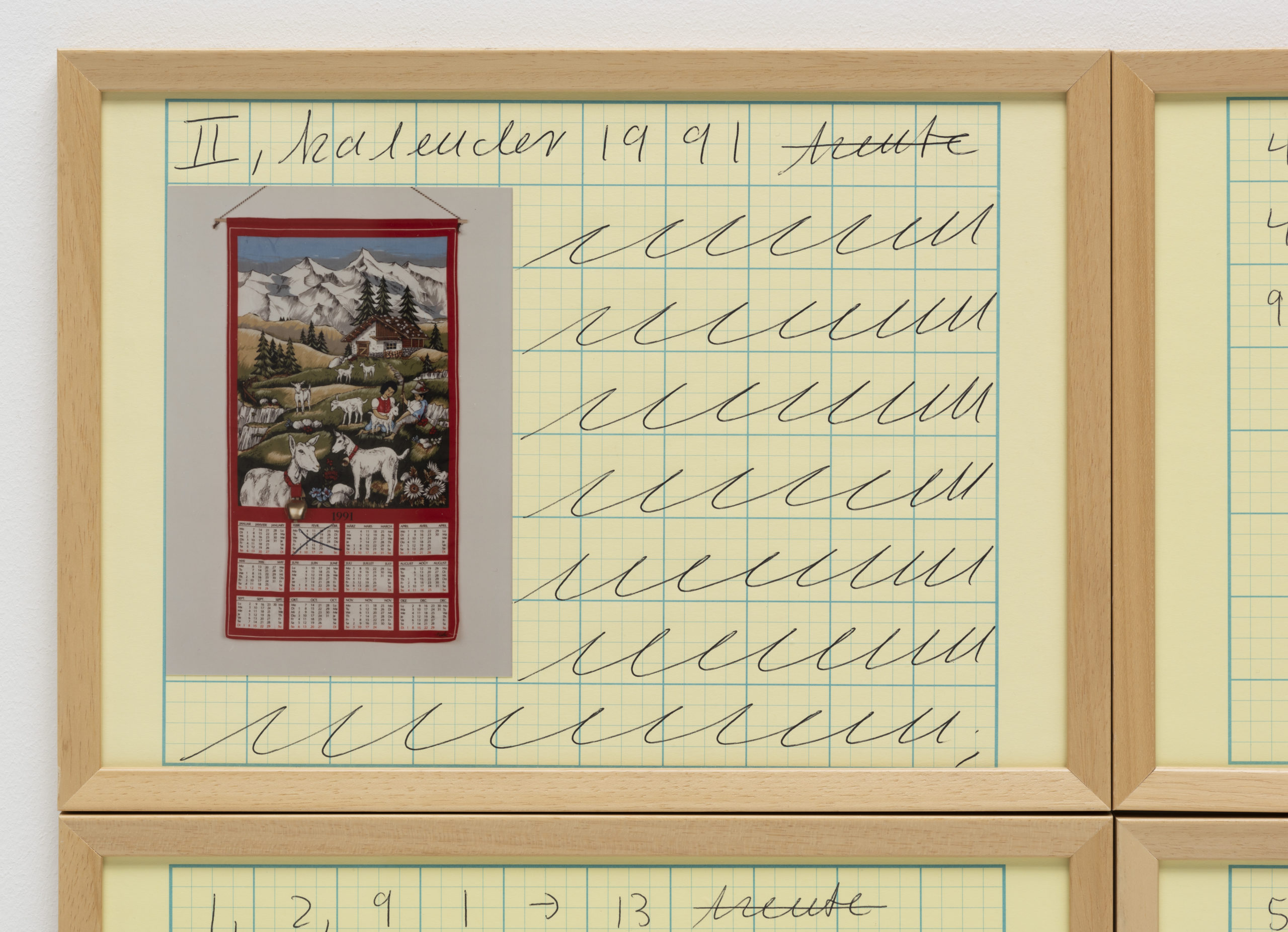

DETAIL: HANNE DARBOVEN, MICKYKALENDER I-XII, 1991

Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / DACS, London 2021 | Courtesy Sprüh Magers

DETAIL: HANNE DARBOVEN, MICKYKALENDER I-XII, 1991

Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / DACS, London 2021 | Courtesy Sprüh Magers

DETAIL: ROCHELLE GOLDBERG

FEAR OF LOSS, 2022

POLYESTER ORGANZA, SILVER PLATED CHAIN, STEEL WIRE, BABY’S BREATH, PAPER FORTUNE, DIMENSION VARIABLE

DETAIL: ROCHELLE GOLDBERG

SAFE, 2019-ONGOING

156 GLASS BOWLS, DIMENSION VARIABLE

MIMOSA ECHARD

PRIVATE PICTURE 2, 2021

PERSONAL OBJECTS, CHERRY PITS, PILLS, WOOL, SILK, NATURAL DYED LACE, CRISTAL, ACRYLIC PAINT, ACRYLIC LACKER

190 x 105 cm (74 6/8 x 41 3/8 in) approx

MIMOSA ECHARD

PRIVATE PICTURE 3, 2021

PERSONAL OBJECTS, PILLS, WOOL, PLASTIC BEADS, NATURAL DYING SILK, NATURAL DYING LACE, SILK ROPE, TULLE, ACRYLIC PAINT, ACRYLIC LACKER

280 x 100 cm (110 2/8 x 39 3/8 in) approx

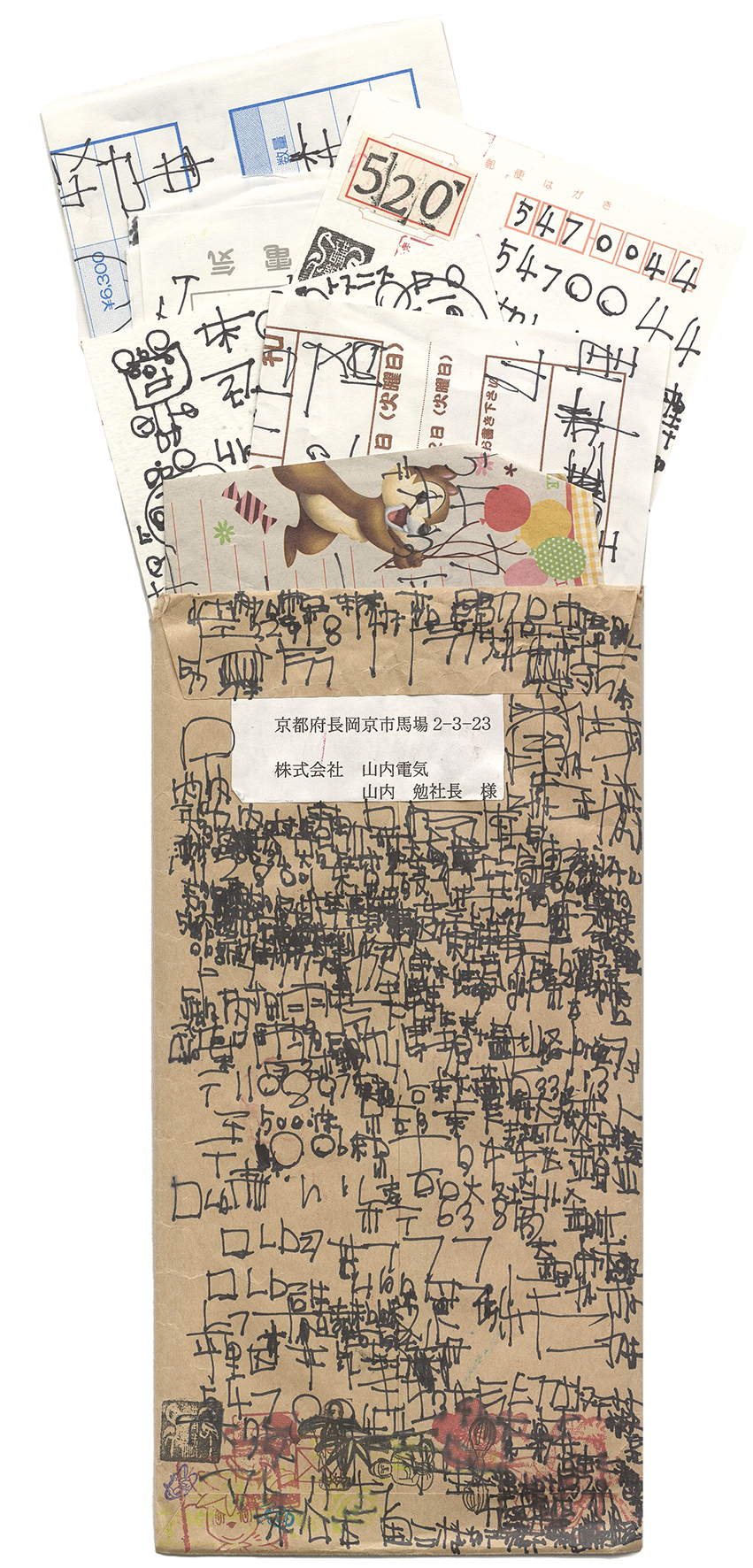

DETAIL: KUNIZO MATSUMOTO

UNTITLED, CIRCA 2010

INK ON PAPER AND COLLAGES, DIMENSION VARIABLE

KUNIZO MATSUMOTO

UNTITLED, CIRCA 2010

INK ON PAPER, AND COLLAGES

23 X 11.7 cm (9 X 4.3 in)

PRESS RELEASE

HANNE DARBOVEN / MIMOSA ECHARD / ROCHELLE GOLDBERG /

KUNIZO MATSUMOTO / ROSE SALANE / MICHAEL E. SMITH

HOLDING ON TO IT

January 27 – March 5, 2022

On a bright, crisp winter morning in the late 90s, my Grandmother brought me to her friend’s house down the street so that she could run some errands. In her typical suburban neighborhood, the house stood out with its wildly overgrown yard and peeling, faded paint. I knew its owner and sole inhabitant as the man who’d bought my Dad’s lime green Toyota pickup truck a few years prior, which my Dad sold to him for scrap due to a wasp infestation in the cab. Gruff and jovial, he often dropped by my Grandmother’s house unannounced — almost always at mealtimes, I later realized — but we’d never been over to his house.

That morning, I remember walking into a space unlike any other I had yet been inside. It was dim. There was no furniture, and only a small sliver of the carpeted floor was visible. On the left side of the first room there was a deep wall of VCRs stacked floor to ceiling. On the right, dozens of tube televisions perched on top of one another. We had to turn sideways to walk through the snaking crevice between these two masses until we reached the kitchen. A harsh light poured in a large window above the sink. There was a five gallon bucket overflowing with individual ketchup packets, a stack of microwaves, a room beyond with leaning bicycles and rusted car rims. Dark, ordered clusters of things I was too young to recognize, and a feeling of compression.

My grandmother mentioned something about breakfast, he mentioned coupons, and we all left for McDonalds. I don’t remember the rest of the day. Much later, I realized that something about this space reminded me of my Dad: the accumulation certainly, but more importantly, the creation of rules to deal with what others consider to be refuse, and abiding by these rules religiously even after they spill over and stifle functional space.

My Dad loves to read newspapers. He has three of them delivered to his office every day. He likes to read things that are urgent, and he likes to save things that interest him that he intends to read later. This rule feels sensible — relatable, even. But his interest outpaces his time capacity for reading. Soon, piles of articles begin to accumulate. And even after these piles reach waist height, overtake a wall, swallow a dining room, he does not revise his rule. Maybe there’s a disconnect in the feedback loop: consideration for what he’ll actually have time to read later never crosses his mind, or it doesn’t cross his mind at that crucial moment when his rule compels him to keep. Or maybe not. Maybe he does know that he’ll never read this wall of paper, sit down for five weeks straight and comb through every word. Maybe something within him just likes the feeling of being inside his collection — of being swallowed by the yellowing stacks.

My Dad loves to drink seltzer. He almost never drinks plain water. He likes single serving bottles from a particular manufacturer. Years ago in his old apartment, he finished one of these bottles and decided to place it on his kitchen counter in the back left corner. He put the next finished bottle to the right of that finished bottle, and the following finished bottle to the right of the previous two. By the next time I visited him, a phalanx of empty bottles completely covered the countertop. And by the following visit, his plastic grid had collected dust. There is no saving-to-read-later for these bottles — no reliving a fizzy sip. This collection is driven purely by the compulsion to make habits become form. Recording daily actions, watching a rule devour space. Habit as a way of being.

For some people, collecting arises from an impulse to imbue certain possessions with special significance. An impulse to create hierarchy between different elements in the collection, and, more importantly, to create division between the collection and everything outside. This type of collecting often arises from faith: a conviction that each element possesses meaning, and that the group of these elements — the collection — is fundamentally greater than the sum of its parts.

But for others, for people like my Dad, collecting is not a hobby and it does not require belief. It is instead an invisible, all-consuming regime of habits — an intrinsic operating system. And like many other deep patterns driven by compulsion, this type of collecting often takes place at the intersection of subconscious fear and desire. The desire to make sense of the world through narrative, the desire to capture a feeling, the desire to control, the desire to preserve and to survive. The fear of emptiness, the fear of chaos, the fear of forgetting, the fear of loss and, ultimately, of death.

These universal driving forces are part of what makes collecting itself so transcendent. Collecting unites two paradigms of the human experience that often seem contradictory: the need to create order in the material world through structure, and the need to believe that mere things possess a higher spiritual essence.

Each of the artists in this exhibition, through widely varying means and mediums, scrutinize these same issues that constellate around collecting: they pursue it not only as a practice, but as a subject. And in doing so, they ask us to consider not only what we collect, but why we collect.

-Nicholas Kokkinis