DETAIL: UNTITLED (STREET LAMP), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 40 x 30 IN (101.5 x 76.5 CM)

UNTITLED (BOW), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 72 x 55 IN (183 x 140 CM)

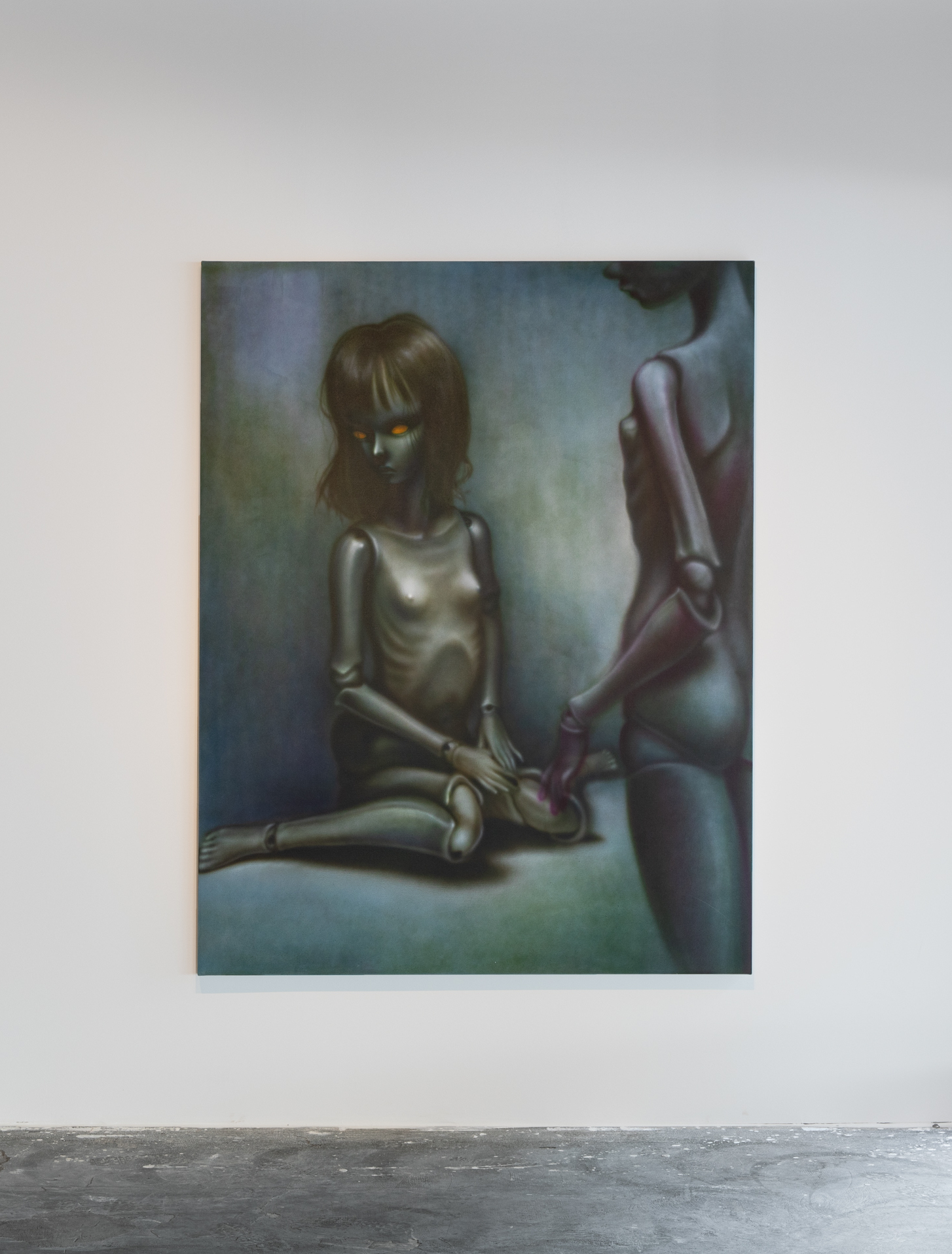

UNTITLED (BLUE CORNER), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 72 x 55 IN

(183 x 140 CM)

UNTITLED (PINK), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 28 x 22 IN (71 x 56 CM)

UNTITLED (RED), 2021

COLOR PENCIL ON PAPER, 7.5 x 5 IN (19 x 12.7 CM)

UNTITLED (YELLOW), 2021

COLOR PENCIL ON PAPER, 7.5 x 5 IN (19 x 12.7 CM)

UNTITLED (DOUBLE EYE), 2021

COLOR PENCIL ON PAPER, 7.5 x 5 IN (19 x 12.7 CM)

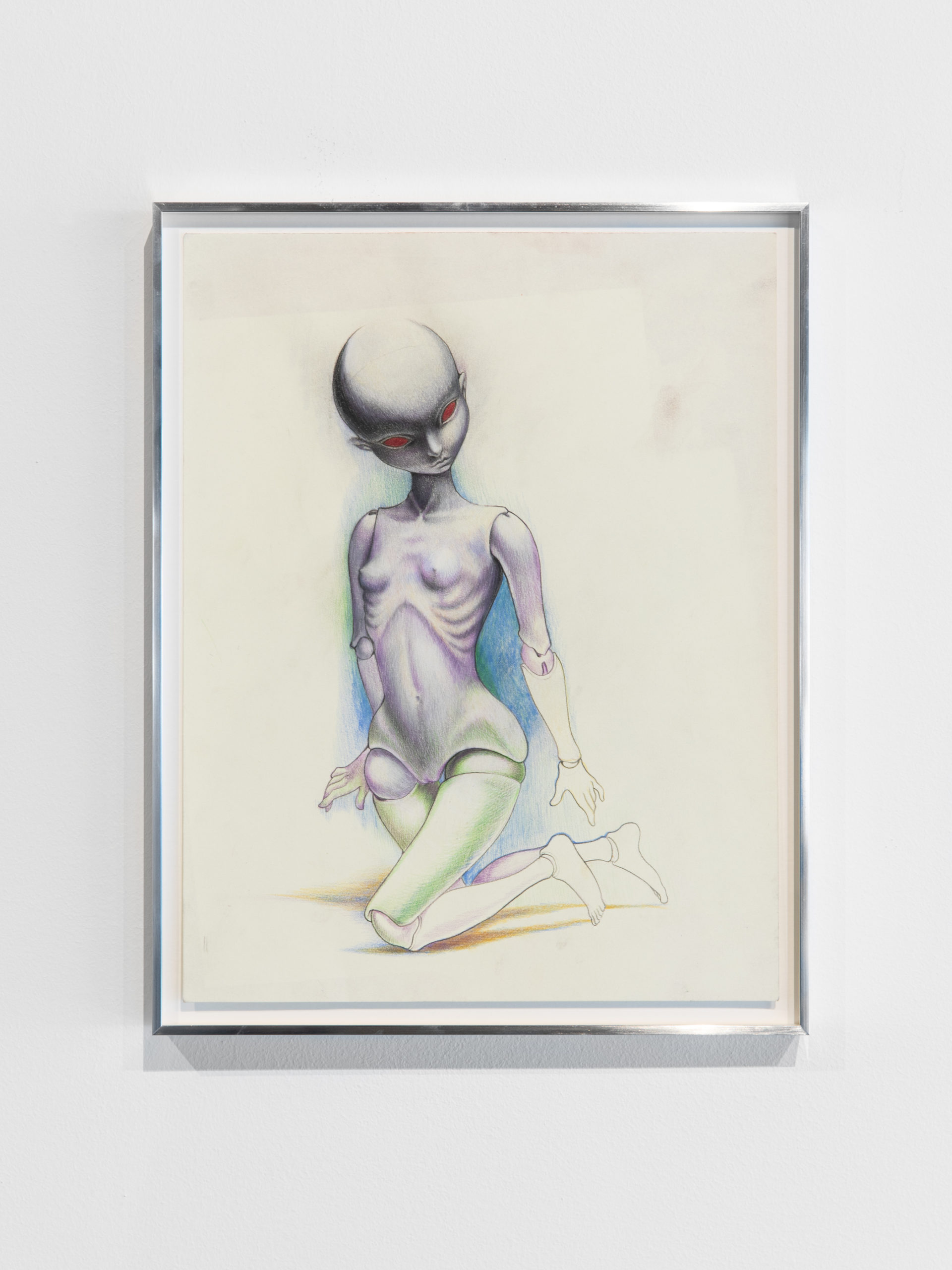

UNTITLED (KNEELING), 2021

COLOR PENCIL ON PAPER, 14 x 11 IN (35.5 x 28 CM)

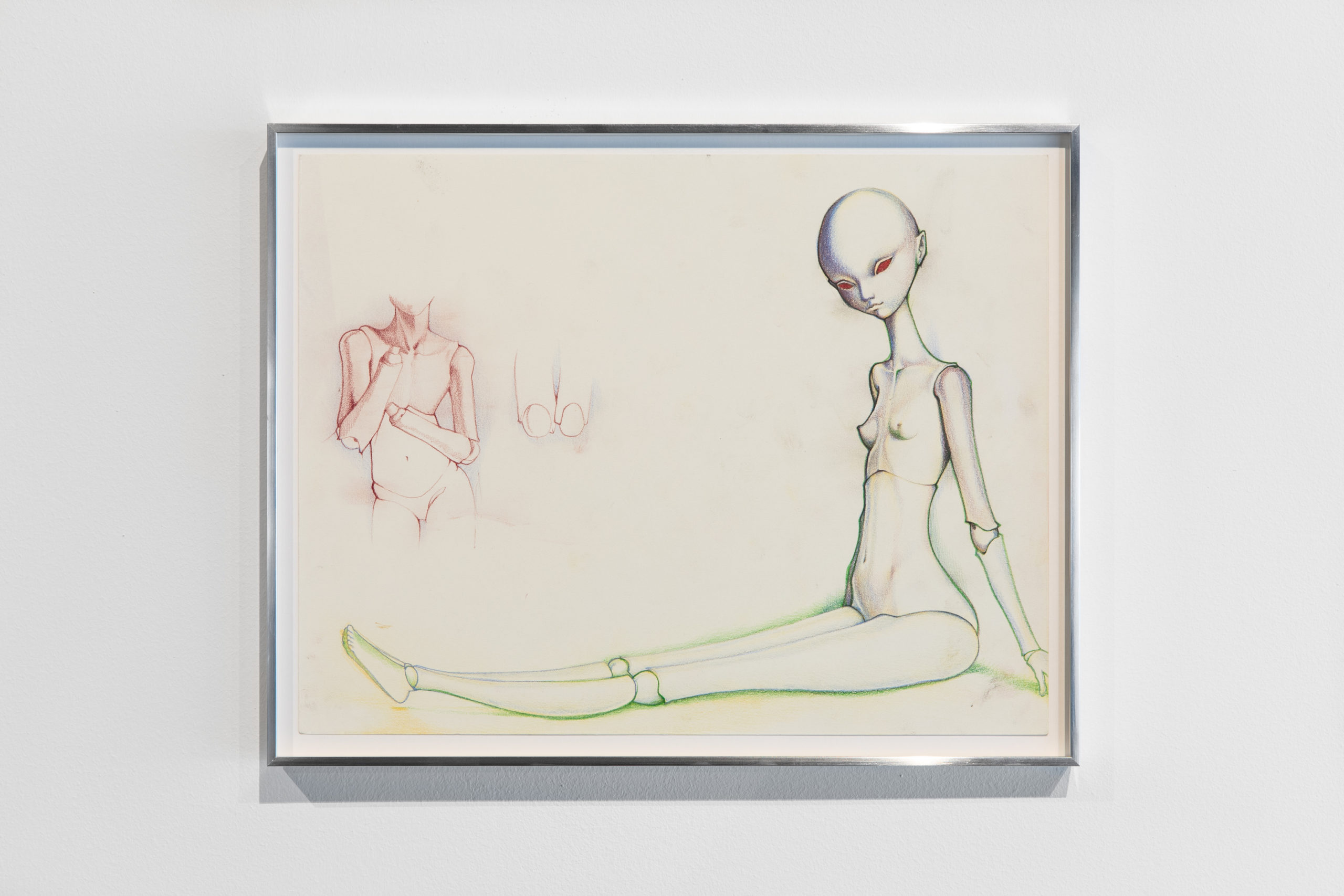

UNTITLED (SITTING GREEN), 2021

COLOR PENCIL ON PAPER, 11 x 14 IN (28 x 35.5 CM)

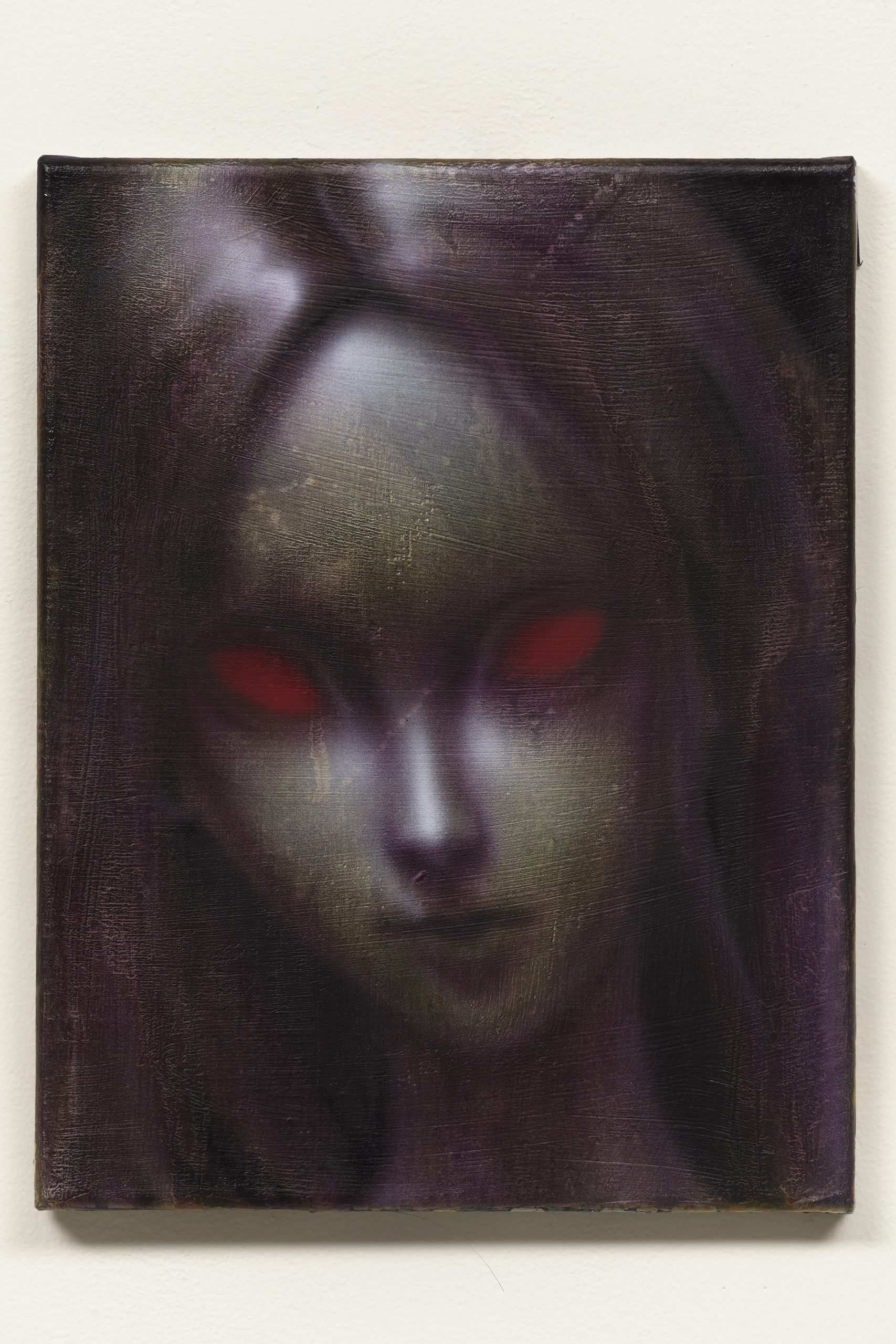

UNTITLED (CLOSE UP 2), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 14 x 11 IN (35.5 x 28 CM)

UNTITLED (RED EYES), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 72 x 55 IN (183 x 140 CM)

UNTITLED (FIELD), 2021

ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 40 x 30 IN (101.5 x 76.5 CM)

PRESS RELEASE

WILL SHELDON

MY SMALL SUPER STAR

September 16 – October 30, 2021

It does not immediately register that they are dolls. I see powerful little girls, ethereal little beings, with bald heads and pubescent breasts and six-packs glowing purple and green. Their nakedness is harsh and extraterrestrial. Somehow they are both vague and chiseled. Frail icons of gymnastic perfection, emerging from the exoplanetary mists. Executing this effect certainly required outrageous skill with an airbrush gun —and Will Sheldon is also a tattoo artist, so this tracks. During our studio visit I feel I am surrounded not by toys but the output of a rather demented life drawing course. A closer inspection reveals seams where each spindly thigh plugs into the pelvis. Those red eyes are not eyes at all. They are holes where glass balls will go.

Sheldon’s new series is inspired by the uncanny world of Japanese ball-jointed art dolls, or BJDs. For the uninitiated this Google search will open an unnerving wormhole from which it is difficult to back away. BJDs exist to be photographed. Mediation ratifies whatever fantasy, so they all have social media accounts. These dolls are influencers, wastrels, superstars. The interval between seeing Sheldon’s paintings and realizing they are dolls is similarly crucial. In it is whispered the secret wish of all who adore and own BJDs: perhaps somewhere (behind the mirror, off Earth) they are alive.

They often look it. BJDs are cast in a hard, porcelain-like synthetic resin that allows for ornate sculpting. Male dolls flex vascular forearms. Ribs and gluteal groups and collarbones are inevitably prominent. Even their minuscule fingernail beds and inner nostrils and nipples are painted peach to mimic human skin. BJDs are denser and taller than Western dolls, and their limbs are articulated with tough elastic so they can be realistically posed. A finished BJD will easily part you with a thousand dollars, especially if you choose to upgrade your doll’s make-up or add an anime-inspired costume. While I know that Japan has a long history of doll fetishization, I find the attention to musculature and the human skeleton in the BJD world unusual. Sheldon explains to me that the trend is in fact not wholly Japanese, but stolen from a German.

In 1933 the artist Hans Bellmer built a mannequin. He created her piecemeal, using ball joints, and posed her for photographs. The doll was monstrous, all breasts and genitals and fat pockets, leg growing out of leg. Bellmer had nearly been persecuted by the Nazis for “degenerate art” and so escaped to Paris, where he was embraced by the surrealists. He openly described himself as a kind of pervy Pygmalion, referring of course to the sculptor in the epic poem by Ovid, so repulsed by flesh-and-blood women he carved an ideal one from ivory, his Galatea. But Bellmer’s work disposed of sappy, Hellenistic idealization. For Bellmer perfection was modularity. Day after day he might remake a woman as he liked, and cherish her stumps and nubs and folds with his camera. He published over one hundred doll photographs from 1936 to 1938, and Japanese artists were captivated. They saw in BJDs the perfect avatars, precisely because they were so easy to dissect and customize. New wig, new me. Even the eyes could be popped out and exchanged.

Sheldon tells me offhand that he was inspired to paint his own dolls with glowing eyes because of something he noticed about the photographs on legenddoll.net, a popular retail site. The eyes are sold separately, he explains, so when the BJDs are photographed under the bright studio lights their empty heads blaze orange like jack-o’-lanterns. I latch onto this detail –there is something ominous about it— but I don’t put it together until I reread “The Sandman” by E.T.A. Hoffman, a story which has kindled nightmares globally since its publication in 1816. The titular villain, the Sandman, is an automaton engineer said to visit children in the nighttime and pluck out their eyes for use in his clockwork beings. The protagonist, Nathanael, falls in love with a woman he believes is this dollmaker’s daughter. When he sees she has no eyes “but black holes instead,” he goes insane. Dolls and simulacra and automata, all these vessels are catnip for the Freudians. What does it Mean that we fear eyeless-ness and creatures with buttons (See: Coraline) or holes instead? What does it Mean, our rich narrative genealogy in which people fall infatuated with their own dead doubles, their statues and machines? The art historian Rosalind Krauss wondered if Hans Bellmer’s work might operate as a kind of talisman against our discomfort: “To produce the image of what one fears, in order to protect oneself from what one fears —this is the strategic achievement of anxiety…”

Near the end of the visit a mutual friend of ours drops by. She says she doesn’t like looking at photographs of BJDs, or any dolls for that matter. They give her the creeps. I say this is a common reaction. The doll-human relationship operates inside a forceful taboo, although personally I don’t find them frightening. “They soothe me,” says Sheldon, and I agree.

-Allison Bulger